Legendary Allagash River Guide Encounters Legendary Supreme Court Justice.

In October 1960, my grandfather, Willard Jalbert, Sr., the "Old Guide," led Justice Douglas's expedition from Telos Lake a hundred miles north along the Allagash River to Allagash Village, another thirty miles east along the St. John River to Fort Kent.

In October 1960, my grandfather, Willard Jalbert, Sr., guided U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas's Allagash River expedition from Telos Lake 100 miles north to Allagash Village, another 30 miles east along the St. John River to Fort Kent. The expedition included Justice Douglas's wife, Merci Douglas, Chub Forster, who organized the trip, and the writer Edmund Ware Smith and his wife. Smith's article about the trip appeared in the May 1961 edition of Field & Stream.

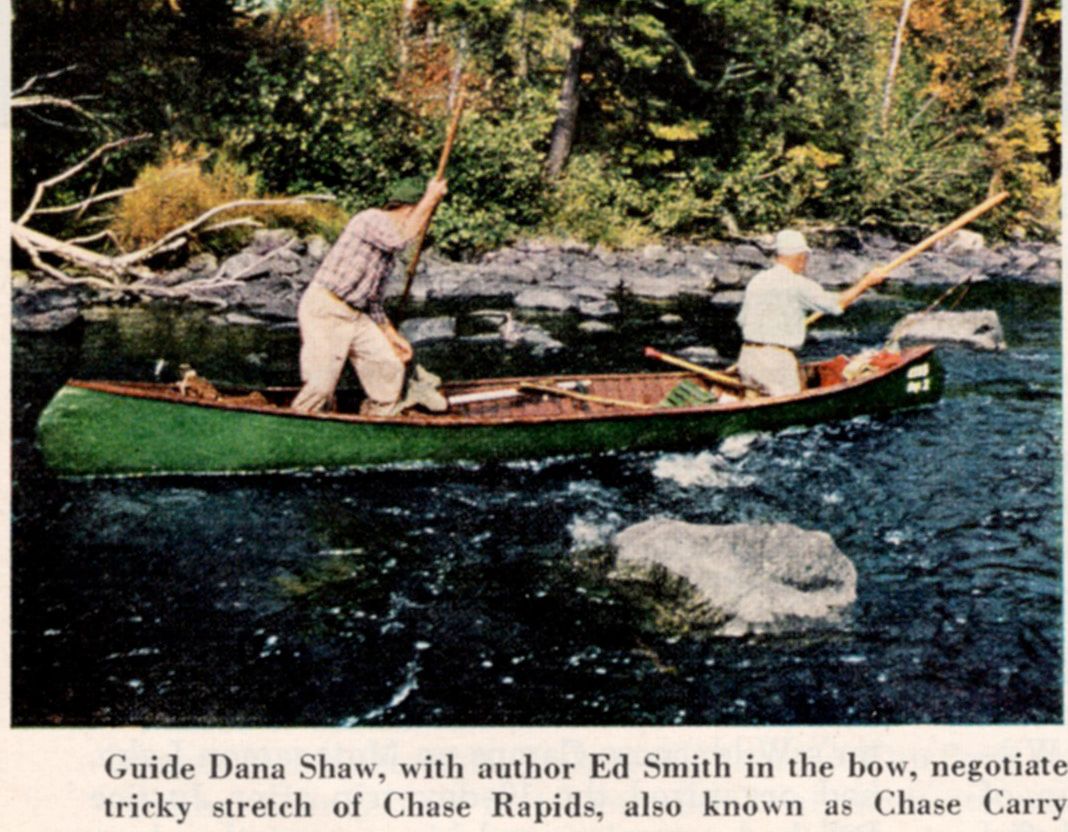

Justice Douglas was as impressed with my grandfather, the "Old Guide," and Uncle Willard Jalbert, Jr., Dave Jackson, and Dana Shaw as Henry David Thoreau was with his guide, Joe Polis. In a collection of essays about his wilderness travels, My Wilderness: East to Katahdin, he dedicated "Allagash" to that river trip.

"None is more skilled as a canoeist than the Old Guide. He paddles like an Indian. The paddle rests on the right leg. The stroke is a quick, short one that seems almost effortless. It's a stroke a man can keep up all day long, hour after hour. The guides of the Allagash can maintain their speed all day long, hour after hour."

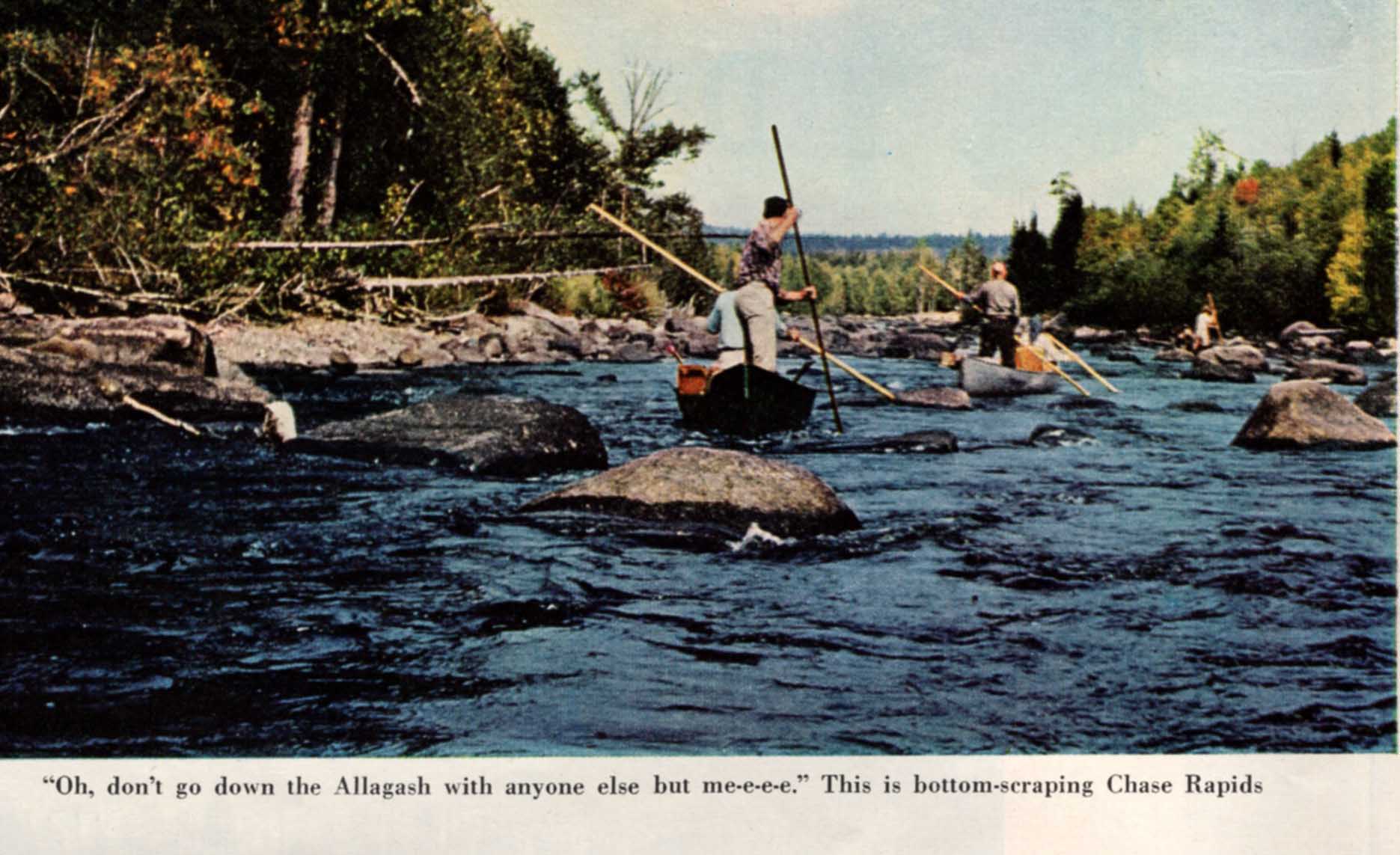

"These guides pole as well as paddle; and their poling is a joy to watch. In a loaded canoe they stand in the stern. With an empty or lightly loaded canoe they will take a step forward. The Old Guide likes an iron cap with a short, blunt spike. The poles are used going up a stream; they are also used coming down through rapids."

"We sat on the shore, watching him maneuver the canoe by standing in the stern to pole through logs and driftwood. 'He's tops,' Ed added. And then pointing to Willard, Jr., David Jackson, and Dana Shaw, the other guides of our group, he added, 'With these four we have the cream of the Allagash.'"

"The Jalberts and the Allagash are almost synonymous in the northland. Willard, Jr., put the matter neatly one night when he related a conversation he once had with a New Yorker. The man inquired a bit nervously if there were bears in the Allagash country.

"'Yes,' Willard said. 'Three kinds—black bear, brown bear, and Jalbert'"

Douglas extended his trip from Allagash Village to Fort Kent. He wanted to camp along the St. John River at Rankin Rapids, a proposed hydroelectric dam site, to understand the project's massive scale. The dam would have created a lake flooding the lower Allagash and St. John Rivers. Later, Cross Rock and Dickey-Lincoln dam proposals were also rejected.

"There are no hundred miles in America quite their equal. Certainly none has their distinctive quality. They will, I pray, be preserved for all time as a roadless primitive waterway."

"Civilization would condemn for all time a wilderness are fashioned by time and nature, nourished by sweet water, and filled with more wonders than man could ever catalogue."

"Part of these wonders is the loneliness, the solitude, the remoteness of the area. Part is the music of flowing water, the purity of the river. Part is the swift, exciting life that flourishes there."

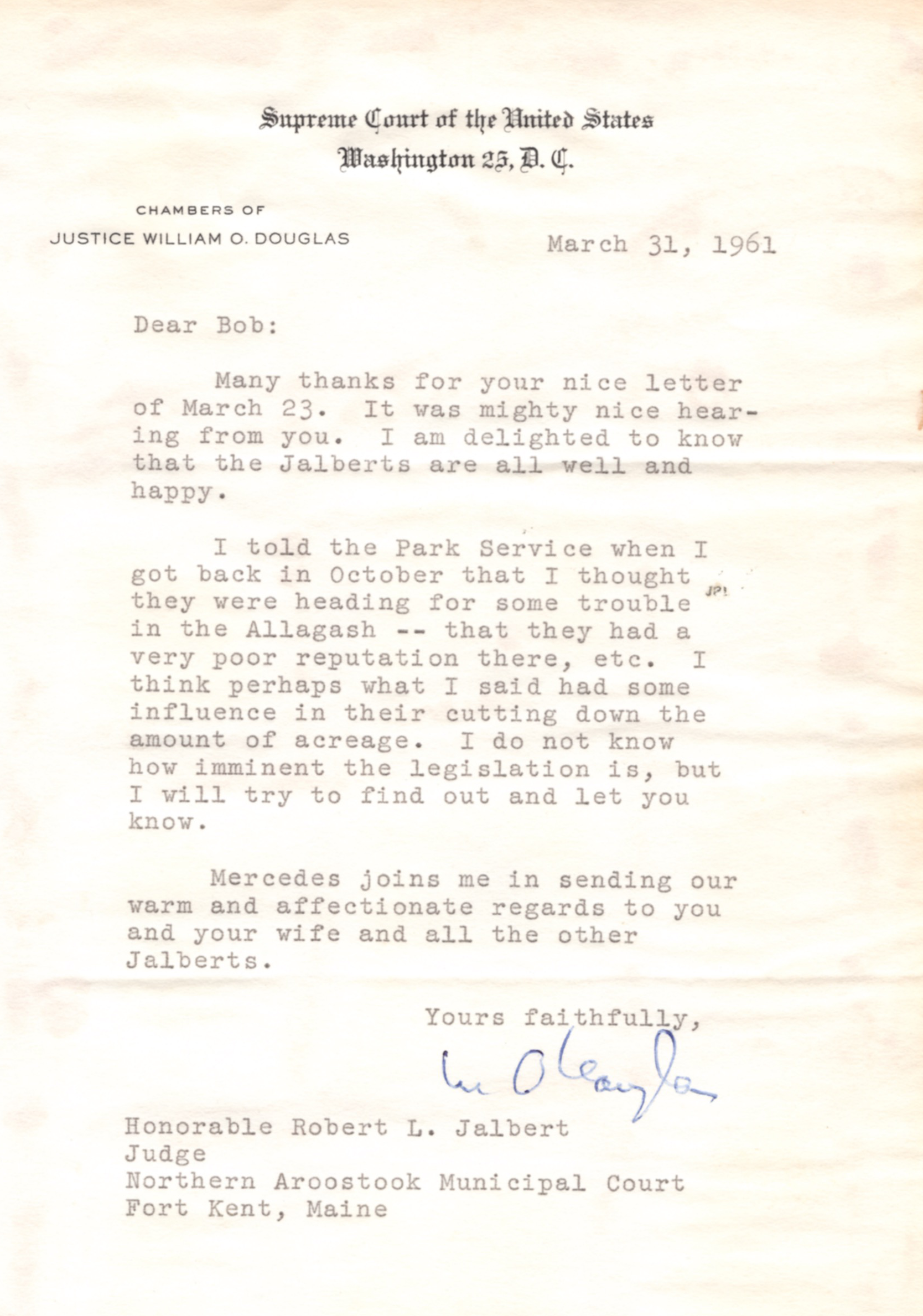

The threat of a hydro dam and logging operations closing in on the Allagash River inspired Douglas to lobby federal agencies and Governor John Reed to protect the Allagash River corridor.

My father, Robert "Bob" Jalbert, was not one of the guides on that trip. However, he was critical in saving it from utter catastrophe: the group ran out of Scotch whiskey when they reached Jalberts Allagash Camps on Round Pond.

He hired a daredevil bush pilot, Arthur Daigle, to fly him in his yellow two-seater Piper Cub from the St. John River shore in Fort Kent to Round Pond, a thirty-minute flight.

That chilly October morning, Round Pond was socked in with dense fog.

Hoping for the fog to open, Arthur circled the lake several times. My father believed the fog wouldn't clear for another hour or two, so they'd have to turn back.

Arthur was patient and a bit...well..."adventurous" is one word, "spirited" might be another, but "reckless" is a lot more accurate.

A hole opened in the fog, a column down to the lake. Before it had time to close, Arthur dove the plane into it. My father's stomach went up into his throat. He clutched the box with the four bottles of Scotch so tight he crushed it.

Arthur pulled up and landed the plane, more like dropping the Piper Cub, less than a hundred feet off the dock.

"A little dangerous," Justice Douglas said to my father. He and the Old Guide had been standing on the dock listening to the circling bush plane, hoping it would fly away rather than attempt to land in dense fog.

"I heard you ran out of Scotch," my father smiled.

Over pancakes, bacon, eggs, hash browns, and pots of coffee that morning, Justice Douglas, my father, uncle, grandfather, and guides, talked about the challenges of preserving the Allagash River and Jalberts Allagash Camps under the dominion of either a state or national park. Impressed by our family's history, beginning in 1871 with my great-parents, Joseph Jalbert and Helen Russell Jalbert, settling on a farm above Allagash Falls, Justice Douglas respected our intimate bond with the wilderness river and hoped we would stay on it for generations.

In the end, it appeared the chances of keeping the hunting and fishing lodge my grandfather, uncle, and father built—including ferrying building materials, appliances, and furniture in twenty-foot Old Town canoes powered by outboard motors ten miles upriver from Allagash Village to Allagash Falls, another twenty miles upriver to Round Pond—might be impossible.

Regardless of the outcome, they would fight to preserve the river. The four of us advocated wilderness preservation in a large and vocal chorus of opponents standing up at every public meeting for more than twenty-five years to preserve the Allagash and St. John Rivers from hydro dam flooding.

Maine Times writer Jack Aley attended one meeting in April of 1977. Impressed by what I had to say in favor of preserving the St. John River, he hired me to guide his group down the river that May. He wanted to see what would be forever lost by a dam. Until I reread this article a few days ago, I didn't realize how long the people from Allagash Village, St. Francis, St. John Plantation, and Fort Kent fought to save the two rivers.

"Greg spoke with passion against the [Dickey-Lincoln] dam, which, if constructed, would transform about 60 miles of the Upper St. John into an 88,000-acre lake. He recalled the coyotes he had heard at Seven Islands and the sheer thrill of plunging down Big Rapids."

Although state and federal politicians dangled the golden carrot of high-paying jobs and recreational opportunities, most Upper St. John Valley people fought to preserve the rivers and family legacies spanning generations. Few people understand the life-orienting power of family and community experiences and stories rising to the level of mythology. Through those stories, the spirits of our ancestors are alive among us.

Here's the link to the May 1961 Field & Stream article "Douglas Down the Allagash" by Edmund Ware Smith.